From journalist to author Orla spoke to Masuma Ahuja about all things Girlhood ahead of the release of her debut book ‘Girlhood: Teens Around the World in their Own Voices’.

I’d like to start by asking you about your career before Girlhood. You’ve worked for The Washington Post and CNN, do you think that prepared you for writing the book?

“I like to tell stories and it’s what I’m good at.”

It’s prepared me for everything that I’ve done. I started my career at The Washington Post. I worked there for a few years then I worked at CNN for two years, and then I went freelance. I learned how to be a journalist and both of those newsrooms. I learned how to do things I do. I also had very good mentors and editors who gave me lots of space to figure out how I like to tell stories and it’s what I’m good at. I stumbled into the space that I like to occupy which is creating portraits of something thematic and bringing in voices of different people

So before Girlhood at CNN, I did a thing where I sent disposable cameras out to women in 20 different countries. CNN is an international news organisation, so they had producers in different places and contacts with local journalists. It was much easier because I could reach out to the person in Japan and say, “Hey, I’m sending you a camera, this is my idea”. The idea was to create a portrait of motherhood around the world. We got women to take photos of their lives. I just wanted to capture what ordinary motherhood looks like. I did something similar with women in the workplace when I was at The Washington Post, so everything was building up. I was learning how to exercise these muscles and to tell and report stories in these ways. That definitely led to the series that then led to the book Girlhood.

Why is it important to you to tell women’s stories?

“Growing up I was the person who bounced between different places.”

I don’t know that I’ve always focused on telling women stories. However, in the last few years, I have focused on women and girl stories. As a former girl and a woman myself, those are stories I’m interested in. I’m interested in human stories. How people’s lives are affected by politics, policy power, the world around them, what ordinary life looks like. Growing up I was the person who bounced between different places. My girlhood in theory was spent between three continents in three countries. I existed as a translator between cultures.

That’s part of the reason I got into journalism was I wanted to help explain how people live in different places and help people everywhere feel reflected in the media they consume. In the stories that they read online, they watch the TV, whatever it is. The reason I stopped at telling stories of girls is because I felt when I was growing up that I didn’t see voices like mine reflected in the media, and I didn’t see stories like mine. The more time I spent with girls reporting one-off feature stories, the conversations I was having with them. Conversations that remind me of my own, I was having at that age. We talked about the books they’re reading or the fight they had with their friend or this is what my parents want me to do, but this is what I want to do. Those stories were just not reflected anywhere in the media. We only saw extremes, if you look especially at parts of the world, I was in like South Asia, the Middle East, you were getting stories of violence, gender-based violence, sexualization victimisation. We have the other side. These are stories of exceptional girls but the vast in-between is where ordinary girls’ lives generally existed. That just wasn’t reflected anywhere

Logistically, how hard was it to find the girls who wanted to take part and organise the book?

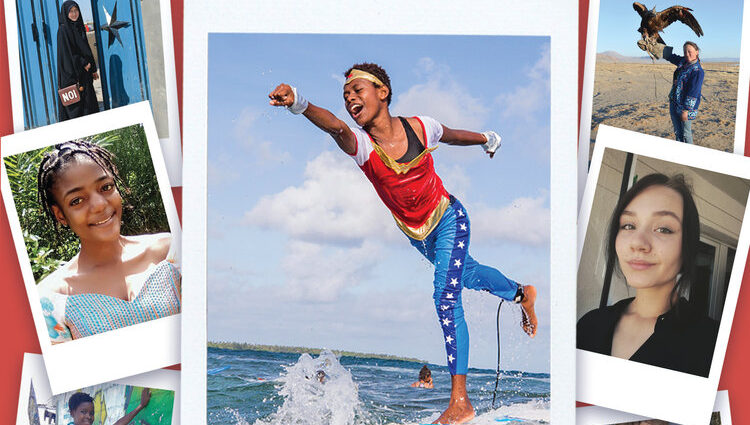

I’m not the kind of person you tasked with being in charge of the spreadsheets or colour coding system, and I had to become that person for the book. Finding, the girls wasn’t very difficult, because I wasn’t necessarily going out on my own. I’d reached the point where I understood how to find someone. I talked to friends and family around the world, I have people friends all over the place. I talked to journalists who work in different countries. I talked to organisations, for example, Alejandro, the girl in Argentina, I found her through her Football Club, which is a football club for girls in Buenos Aires. Claudia, the girl on the cover, who’s surfing in the Wonder Woman suit is from Vanuatu, and I found her through the Vanuatu Surfing Association. Communication was not a challenge, but it was difficult. Most of the girls I was communicating with via text or email, because just with time zones. That’s part of the reason diary entries are wonderful because I gave them the space to define how they want to share their lives. I didn’t have to sit there and ask a million questions. They got to negotiate with lots of instructions from me. Then we did follow up interviews.

Had any of the Girls kept a Diary before the book?

Some of them had kept diaries but for some of them, it was a new idea. I explained what we were trying to achieve. My instructions were always here are some guiding questions. Also, you can just ignore every instruction I’ve given me and write about whatever you want to write about because this is your space and sometimes that happened where I’d give instructions to tell us what happened, who did you talk to today? How are you feeling? Why are you feeling this? Like what happened that made you feel this way? Then they would just go off and, write about, you know, some tests they took at school, but that would be like the bulk of their journal entry because that’s what they were thinking about. That was absolutely fine.

Some of the girls had had quite harrowing experiences or live in dangerous places, how did that impact your mental health, did you ever worry about them?

It was a thing that was very present for sure. What I was very conscious of was that I didn’t want any girl’s life to be represented solely by the circumstances around her, or things that had happened to her or happened in her community. Because they’re all more than that. It is a trap we tend to fall into in the media, defining people by the worst of the places they live and flattening people to single parts of their lives, which might be very big parts of their lives. Also, people who live in conflict zones also have families they love and play with their children, they play with their friends or they have books they love to read /there are parts of their day that are still impacted by the events but are human and things we can all relate to. For example, Merrison in Haiti talks about gang violence in her neighbourhood and is also a chess champion.

Did any of the parents have any apprehensions about their child taking part in the book?

“People’s lives change and they should feel comfortable with everything that’s included.”

I try to be very transparent with everyone I work with about what I’m doing and what it’ll look like. So explaining to parents if the girls weren’t adults themselves, what was what this was, so everyone felt okay with them sharing these stories. I kept in mind that they’re young girls, and their lives are going to be hopefully long. This is going to be a thing that exists for the next 20 years. People’s lives change and they should feel comfortable with everything that’s included. Their parents and guardians should also all be on board because this shouldn’t be a fight for anyone. This is going to be printed, so it shouldn’t become a problem in anyone’s life.

Have you kept in touch with any of the girls?

I have. I don’t talk to them every day but I’ve kept in touch with them. I wanted to get the book out to every girl in it. So it was like a nice way to check in with them / I’ve checked in every few months just to see how things are going. Some of them have reached out to me for advice about applying to uni or applying for internships. I’m always happy to help them if I can just be an adult, older sister figure in their life now.

Did you keep a diary growing up?

I did, during my childhood, I still have a journal that I write in. I’m not a regular diary writer, it’s very much when the moment moves me. In recent years, I was travelling a lot. So it used to be my ritual when I was in an airport, it would be like a good in-between time to sit down and write.

What advice would you give to your younger self?

There is a space for you in the world and your voice matters, and you matter. There’s so much messaging that tells girls to be smaller, quieter, take up less space in the world. When you’re, when you’re in school, you’re told not to ask too many questions, you’re told not to be so bossy or so ambitious, or whatever it is. And the world needs all of that and more. There’s space for you. Just like just keep going, you’re not alone in it.

“the power of girls, that’s the thing that I hope people take away.”

What do you want people to take away from the book after they’ve read it?

I hope that every person like me when I was putting together the book, caught glimpses of themselves in different parts of the world. And saw themselves in girls, they might not have expected to see themselves in. Whether you are a girl, an adult woman, a man, a boy, whoever you are, gender-neutral. These are just stories of what it is to be a human in the world. Also the power of girls, that’s the thing that I hope people take away. Girls or girls and their interests are often taken very frivolously, and not taken seriously. I hope this book can help shift that just a little bit.

Girlhood: Teens Around the World in their Own Voices is available to pre-order now and will be released 9th February 2021.

Orla McAndrew

Feature image courtesy of Masuma Ahuja. No changes were made to this image.

1 Comment