Eva Castanedo

For the last five years, UK university campuses have been the site of numerous teaching strikes. The most recent strikes, beginning in February and continuing throughout this month, are expected to be the biggest yet.

Despite their increasing frequency, there are legitimate grounds upon which we can question their effectiveness.

What are the strikes?

The University and College Union (UCU) is currently participating in 18 days of industrial action in February and March, due to issues regarding pay, working conditions, and pension cuts.

With tens of thousands of lecturers and other academic staff partaking, the University and College Union has called these the “most disruptive strikes ever”.

The logistics of university strikes

Importantly, university lecturer strikes work differently from those in other industries. Take the railway workers’ strikes as an example: when they strike, trains do not run and hence users are directly affected by the industrial action. But railway companies also heavily feel the consequences of industrial action. When their workers strike, ticket sales and revenue fall and these companies are obliged by law to refund customers. In other words, railway companies lose financially when workers strike.

“how effective are these strikes for workers, if universities do not notice any immediate financial effects?”

When it comes to lecturer strikes, on the other hand, strikers do not receive their salaries, meaning universities save the money they would otherwise have paid out. Yet crucially, students still have to pay their tuition loans. An investigation conducted by The Tab this summer found Russell Group unis saved £11 million in withheld pay whilst lecturers were on strike last university year. This begs the question: how effective are these strikes for workers, if universities do not notice any immediate financial effects?

Implications for students and staff

Some institutions maintain that lecturers would rather get an acceptable settlement with their employers, and employers do not want to see their activity being disrupted. Cardiff University, for example, sent out internal communications to its students with this sentiment.

“The question is, then, in an era of strikes, who is looking after the students?”

As much as strike conflict is a problematic situation for both educators and educational institutions, formal negotiations mean that they can safeguard their interests in a setting where they have some protection and coverage – and where both sides can be heard.

Students, however, are not given a voice in this matter. Student perspectives on the strikes have varied over the years, and diverse opinions remain. In 2023, it can often seem like solidarity is harder to feel. Of course, students understand the situation their teachers are in and respect their lawful right to strike. But our education has already been severely disrupted during the last few years because of Covid-19 as well as strikes. The question is, then, in an era of strikes, who is looking after the students?

The future of university strikes

At times, it can feel as though no one is winning with these strikes. Shaky relations between employers and employees are evidenced by the repeated failure to reach lasting outcomes on negotiations over pay and pensions.

Some public figures, like Charlie Jeffery, the University of York’s Vice-Chancellor, point out that the root cause of the problem is that University funding is not high enough to cope economically with the Union’s demands, especially when it comes to the portion of the income that corresponds to undergraduate student fees.

Maybe the answer lies elsewhere, then. Perhaps employers and trade unions should come together against the government to set up a sustainable home undergraduate funding system – one that puts University boards in a position where they can implement better working conditions in an economically sustainable way.

Lecturers and staff are immersed in energy-draining industrial action with the prestigious reputation of UK universities in danger. Ultimately, students’ one-in-a-lifetime experiences of degrees are deeply disappointed that their time at university is being disrupted.

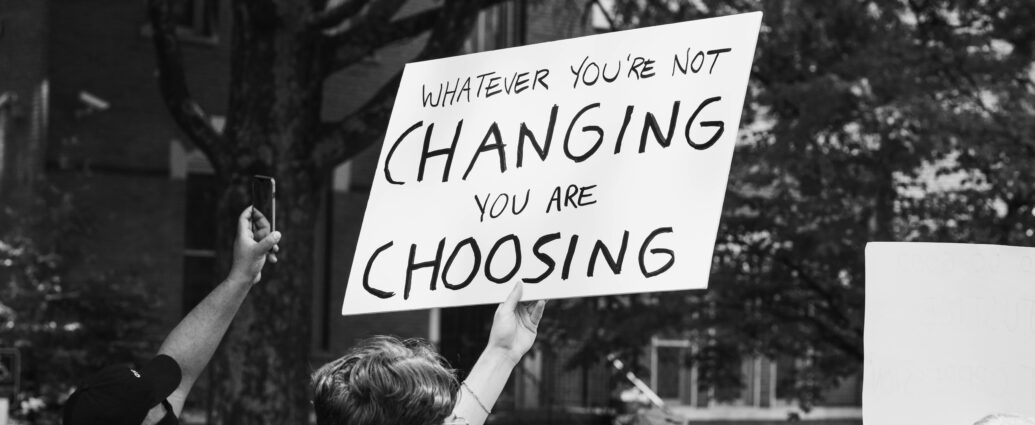

Featured image courtesy of Corey Young via Unsplash. No changes were made to this image. Image license found here.